What are ‘good’ legal designs, and how can we make more of them?

In this chapter, I present the mechanics of quality legal design work. This includes the tools, insights, frames, patterns, and principles you can use to make successful legal designs. It’s a collection that’s meant to help you create high quality new legal things, by borrowing from what we’ve already been learning at the Legal Design Lab.

Use Design Mechanics to jumpstart your design work

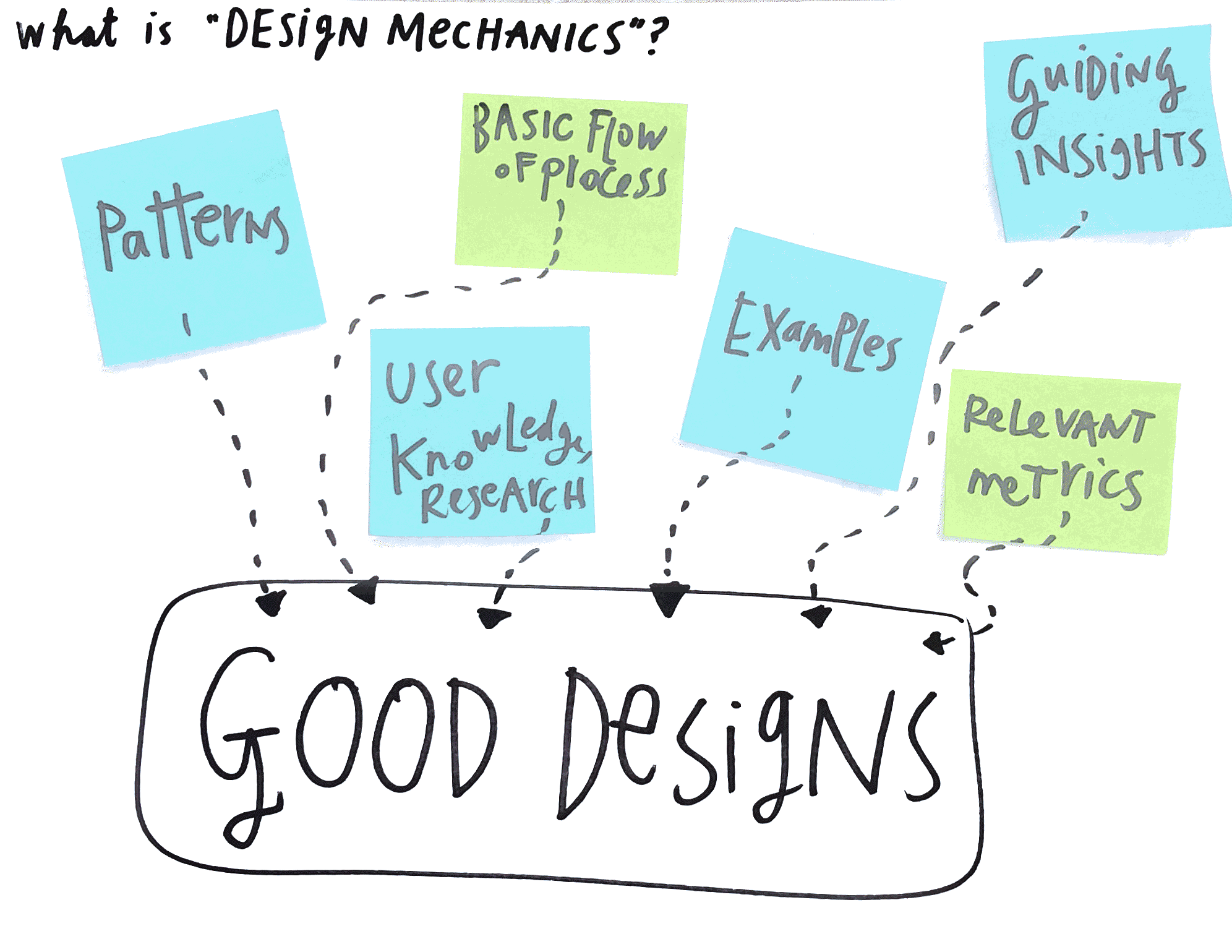

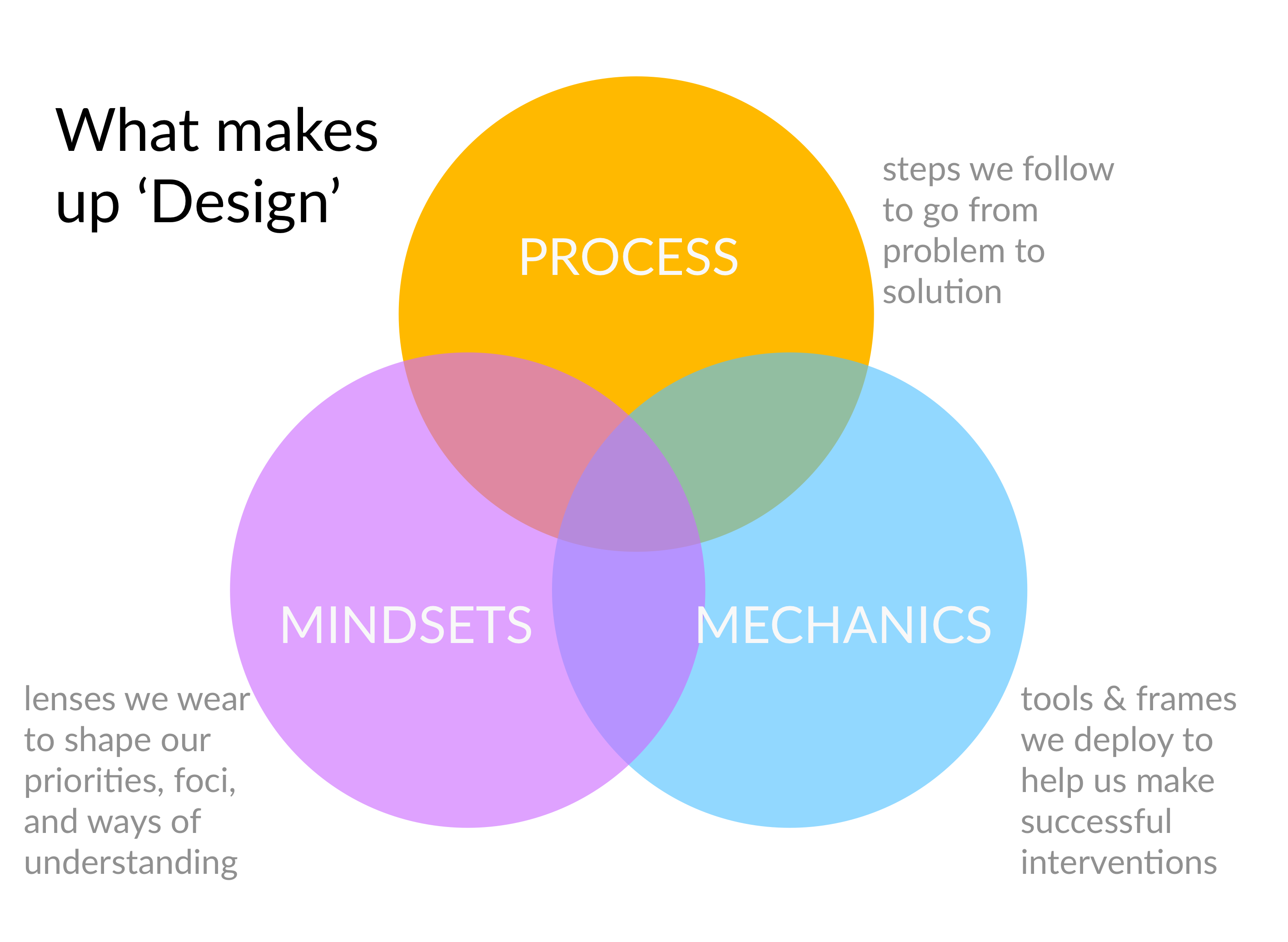

‘Design Mechanics’ is a term I created to encapsulate the insights, research, tools and patterns in a given domain. These are the ingredients that can go into a design process to get to better outcomes.

If your goal is to implement new products and services, then you need to be thinking about design mechanics. Using the Design process (see Chapter 3) and design mindsets (see Chapter 2) can help you find and test great ideas.

Design mechanics speeds up this work, getting you to better designs faster. You learn from other’s efforts, and charge your work with established principles, insights, and patterns that have already been shown to be successful.

Design mechanics are valuable because they tap into the hive mind that’s already been working around your challenge area. Unlike process and mindsets, they are more specific to a certain domain. By learning from others who have already been experimenting with legal design and related fields, you can jumpstart your own work based on their findings (and failures).

In that spirit, I use this chapter to present the insights, patterns, and findings that I’ve learned over the past years of doing legal design work. I have curated materials to show you not just how to follow the steps of design, but how to make good products and services that will meet your users’ needs. I will add more mechanics here periodically.

The Legal Design mechanics presented here include:

- Principles for “Good” Legal Design. These are the 6 main principles to use to review what you’re currently offering, and craft new products and services that will provide a better user experience.

- User Requirements for Legal Services, and Core Insights about User-Friendly Legal Designs. These include insights into how Laypeople relate to the law and want to use it, how to make legal services that laypeople actually want to engage with and use

- Legal User Typology, which (unlike the previous category of mechanics) spells out the key differences in ways that various people interact with legal tasks and products. These differences lay out the varied types of support that we need to provide to make legal products and services work for different kinds of people.

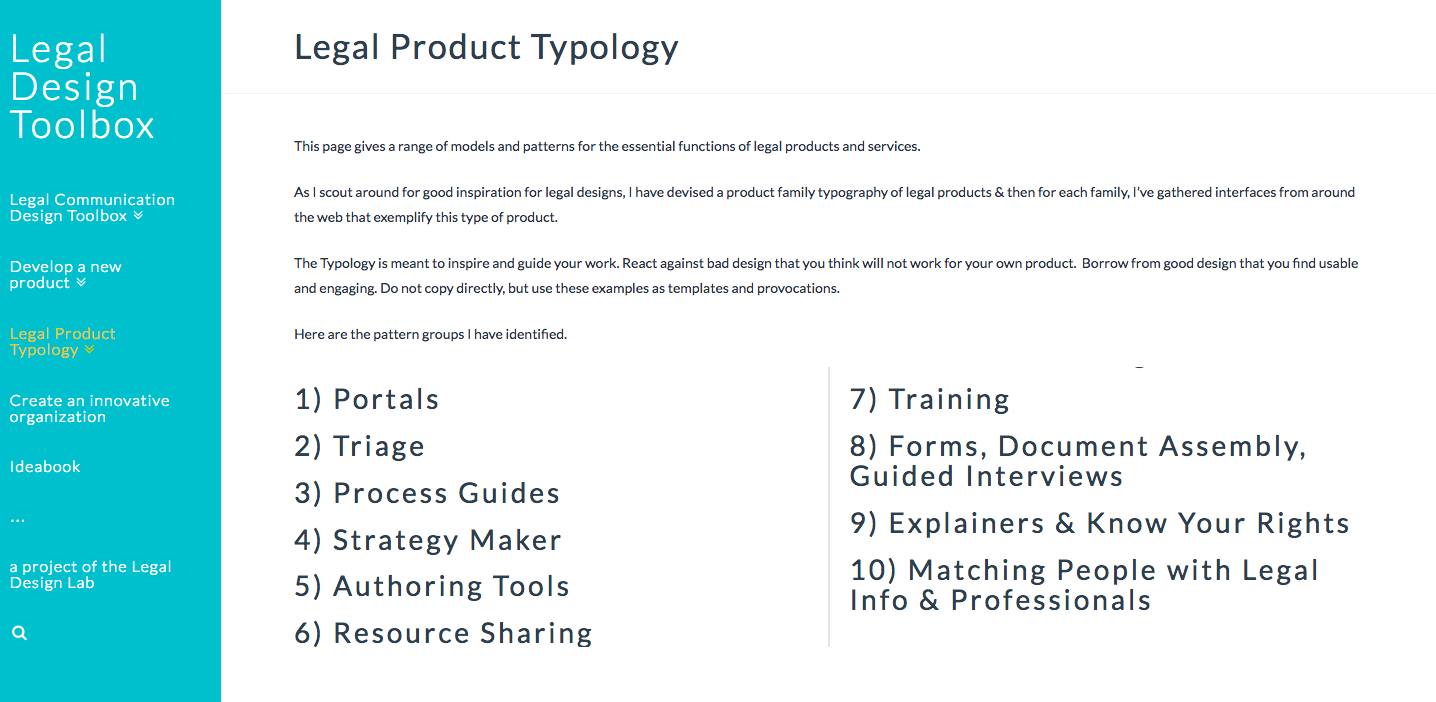

- Next-Generation Legal Design Typology, that lay out the kinds of products and services our testing indicates that users need.

- Good interfaces for digital legal services, that show how best to provide legal help online.

In the future, I’ll add in more legal design mechanics. These upcoming sections include:

- A pattern library of types of design elements and products

- Examples of new generation products and interfaces, that can be of inspiration to future work

- Case studies of how these mechanics have been used to create successful designs

Six Fundamental Principles for Good Legal Design

Over the past five years I’ve done many design workshops, classes, hackathons, and development projects about how to make the law more accessible to people. In all that work, I’ve watched many distinct themes and patterns emerge.

In particular, these six principles have emerged as fundamental lessons for what makes both ‘normal’ and ‘corporate’ legal services work better.

1. Make the users of legal services more empowered and intelligent

Many people want more input and oversight of the process they’re going through. They want a collaborative relationship with their advocate.

Good legal designs will bolster this person to understand what’s going on, and be strategic in making their way through it. Give them more tools to comprehend the legal system, spin out scenarios about how it can play out, and to work with their lawyers.

2. Provide process-based views of legal work

Show a person how the system works step-by-step process. Like a board game, show them the various pathways, and what their start and endpoints are. This will empower professionals and laypeople who are working on a matter.

Presenting the legal design as a process means laying the pathways and steps out systematically from a user’s perspective — a to b to c, all the way to the resolution point z. Rather than describing what you’re offering just in paragraphs or in abstract terms, get concrete and process-based, presenting it as a board game of how a person would proceed from start to finish.

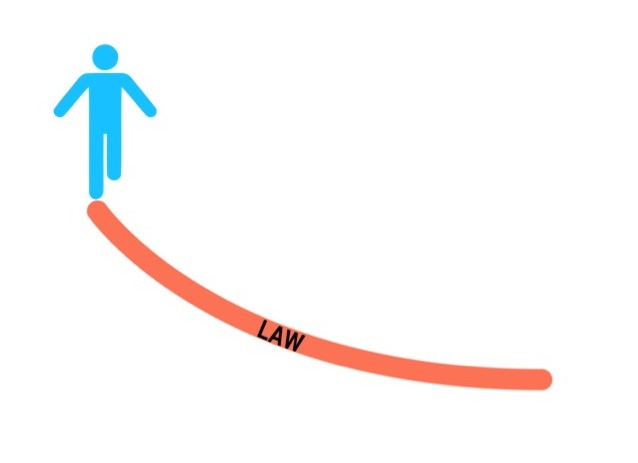

The metaphor of a journey is a powerful and resonant one for laypeople encountering the legal system. A good legal design will use this journey metaphor, and clearly show what the user’s given path is, so the user will understand what’s happening, where it might lead, and who is doing what.

3. Foster a collaborative relationship between the person and the advocate

In the past, lawyers often times thought of themselves as the ‘adult’ and the client as the ‘child’ — hiding details from them, not explaining why they were doing things, and not expecting them to contribute much.

What we see in our user research, though, is that many types of people want to have a larger role in their own advocacy. They want to gather information, understand their options and strategies, and to oversee the process that their lawyer (or other advocate) is carrying out for them.

Good legal design should provide tools, strategies, and templates for relationships that can be more two-way rather than one-way, and that give people a sense of transparency and of dignity when interacting with professionals who are representing them.

4. Always give the Bird’s Eye View that Swoops In

When we talk to lay people about what they want to be better informed, they consistently request a map. They want to see a zoomed-out version of what the legal terrain that they’re on looks like, as if they were using Google Map.

Giving a bird’s eye view to a person lets them understand context, and why they are doing what they are doing. Good design will give them perspective and transparency about the system they’re embedded in, and what paths are available to them.

5. Be Simple on the Front, and Smart at the Back

Any tool or interface should give a guided, limited path for a person to follow. People don’t want a lot of choices to make — they want to be told what the best strategy for them (and for most people) is, and then to follow it. Giving too many options or information hinders engagement.

How to present this simple, streamlined guidance responsibly? Harness research, data, and user testing to figure out what the best way to simplify content and to suggest defaults. Do the work of making strategic choices and boiling information down to its essentials, rather than dumping all the content and choices on the end-user.

Or, even better, learn from a person’s past behavior and expressed preferences to give them the streamlined experience specific to them.

You can still present the details, or the non-default choices in links and stages — so that they are there, but still allow most users to flow through the default path.

6. Provide Multiple Modes that Let People Customize the Experience

We know that not all people like to take in information in the same way. Some people are visual, others like to read. Some like to be totally in charge and dig into reasons and background information. Others want to stay high level and delegate analysis and decision-making to others.

Other key differences: people who are tech-enabled, or even mobile-only, versus those who want paper hard copies. Or those who have limited English proficiency or a disability. See the section below, of a Legal User Typology, to read more.

A good design will make the same content available in multiple modes, to account for these different types of users. That means investing in pushing the base content onto multiple platforms: papers, posters, brochures, reports, mobile-friendly websites, SMS, Facebook, WhatsApp, and beyond. Wherever your target users are, go there and present your content in that format.

Don’t just create a PDF text document of your information and resources and leave it there. Make the content come alive, send it out through many channels, and give your user the ability to experience it in multiple languages, text and visual media, and with both the quick-high level version (see the Simple at the Front principle) with lots of details a click away for the questioners.

This may sound like a lot of work, but if you truly want your audience to find your excellent legal information and resources and to be able to use it — it’s worth investing in creative, wide, and customized versions of it.

User Requirements and Insights

When it comes to engaging a layperson — especially someone who’s unfamiliar with the legal system and doesn’t know many lawyers personally — there are a shortlist of user requirements. A good legal product or service will abide by these requirements. They enhance trust, reduce apprehension, and promote engagement.

There are some common findings about what people want and require from legal services. These apply to most all users when it comes to providing better legal services. Here, I present them in the voice of the users.

- TL;DR: I do not want to read long pieces of text. Not lay people, not legal professionals. Solutions must break up text into usable and manageable sized chunks. And supplement text with visual media, interactive features, and other ways that adjust from the Big-Blocks-of-Text default style. Make it Visual. I want pictures, and text that is quick and clear.

- Give me stories, give me anecdotes. Even if I don’t trust Yahoo Answers, I want to read through it and see what real people have experienced in similar challenge areas as I am in. I want peer-to-peer experiences, or ones that feel like its coming from a peer. I want to hear from others whom I can relate to. For the lawyer, this means offering Peer-to-Peer type of advice in some instances, and switch to Expert-to-Lay communications in other ones. There must be several different types of modes of giving communication & providing services.

- Show me a menu of what’s available, and help me choose. Rather than give detailed explanations of the law, or long undifferentiated lists of information, I want a boiled down, personalized menu. I want clean and limited options, and then tell me how to evaluate them. Curate it for me. Give me a Master Game Plan that is simple, and that can be filled out with my choices, and all the detailed instructions and explanations that go with them.

- I want transparency! Make it clear what steps will be happening, what I can do, what you will be doing. Also, tell me how much it will cost, how long it will take, and what will be required of me. In design-speak, this is about giving people perceived control — the feeling that they do have oversight into what is happening to them in the system, that can give them a sense of dignity. In legal-speak, this is about procedural justice — feeling that the system is treating them fairly, according to clear and respectable rules.

- Let me use expensive experts selectively. This one is more dependent on user persona type, but it applies to most of them. The attitude goes: I don’t want to talk to lawyers for everything. I’d rather hack answers and strategies together myself when it’s appropriate, and then use lawyers very selectively. That’s because with a lawyer, I don’t know how much it’s going to cost, I don’t know whether I can trust you versus everyone else, I don’t know how this is going to spin out in the future. Give me control over what’s happening, but then also let me hand tasks off when I’m over my head.

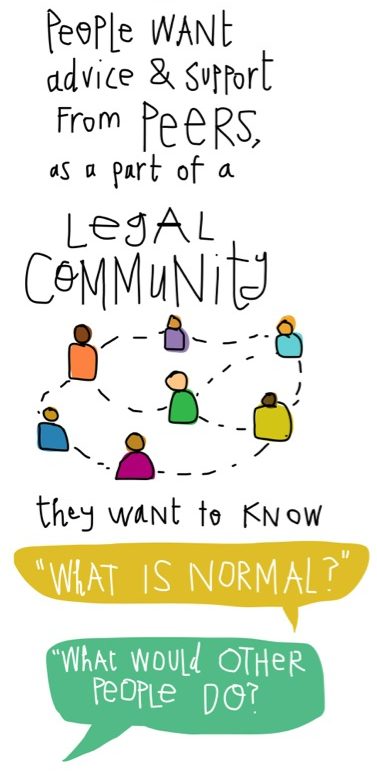

- I want to be normal, tell me what other people would do. I want to know what kinds of behaviors and outcomes are normal. I want to know what course of action most people choose, and I’ll probably take this course or a slight customized variation of it.

- I’m not stupid, I want your respect. I know I’m ignorant in this new terrain of law, but I’m still sensitive to being ‘talked down to’. It’s a weird mix. People know they’re not law-smart, and they know they need help from experts, but they still want to be treated in a non-hierarchical way. They don’t want lectures, they want collegiality and a sense of collaboration. They feel vulnerable and want to know their advocate is listening to them, respects the uniqueness of their situation, and is telling them the whole truth, with respect for their intelligence.

How lay people experience the legal system

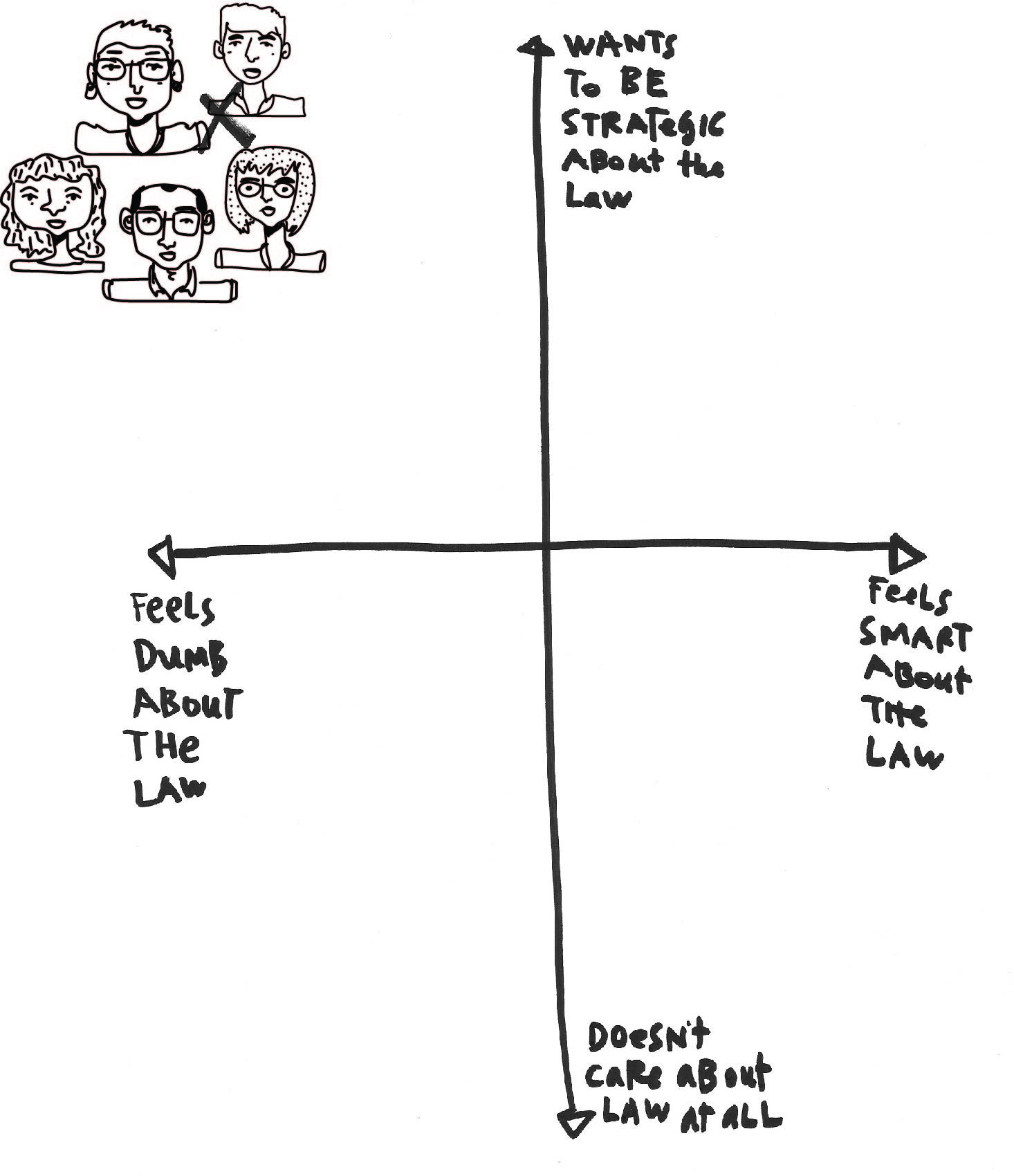

Many of these user requirements derive from some fundamental trends in lay people’ experience of the legal system. One of the most profound one is summarized in this matrix. People want to to be strategic in the legal space. They’ve seen the TV shows and the movies. They know the consequences of getting legal stuff wrong, or of navigating the system well. They have high aspirations for using this system to their advantage, and being smart.

The problem is they don’t feel smart in the world of law. Even if they are professionals with higher degrees, in the area of law, they feel ignorant and off-kilter. This feeling of dumbness is exacerbated by the emotions of the problem they’re trying to deal with.

The problem is they don’t feel smart in the world of law. Even if they are professionals with higher degrees, in the area of law, they feel ignorant and off-kilter. This feeling of dumbness is exacerbated by the emotions of the problem they’re trying to deal with.

Some dominant frames emerged during our user research, across all types of users. These are common themes that we hear repeatedly from all types of users in our legal design work. These are overarching frames and mental models which can help us build more engaging & user-friendly legal products.

One powerful frame is that of “Getting It Right.” It’s about staying on track, not falling off this precipitous, balance beam of a legal process.

The fear is that if you slip up, go off track, or make a small mistake, all of your effort will be for naught. You will be in dangerous territory of penalties, lost chances, and bad outcomes.

The fear is that if you slip up, go off track, or make a small mistake, all of your effort will be for naught. You will be in dangerous territory of penalties, lost chances, and bad outcomes.

Legal services should be helping the person to walk this line well & confidently. They should provide assurance that the person is doing the right thing, avoiding pitfalls, and is going to get to the end goal intact.

Another powerful frame is “Following the Crowd”. People express an urge to be where most other people are, to be normal, average, and following the trend. This can mean literally making choices and doing legal work while being with a group of people they trust. But it can also mean that they want to know what most other people tend to do in situations akin to their own, and using this data point as a guide for what their own preferences are.

This frame could also be expressed as “Just Tell Me What’s Normal”. Since most people don’t have personal familiarity with the legal system, and haven’t had many close experiences or anecdotes with legal procedures (aside from the few types that they might see on tv or in movies), they don’t have a sense of what ‘normal’ decisions or behavior looks like. It is hard to form a strategy or assess options when you don’t have a baseline of what is too risky, too cautious, usual or strange. This leads to the need for peer stories, data about what crowds do and what outcomes they experience, and a hunger for examples.

A final dominant frame is “Give Me Shortcuts to Legal Advice”. Or, “Don’t Make Me Talk to Lawyers.” This comes with a resistance to speak to lawyers directly, out of concern that this might lead to an engagement that’s difficult to manage, that’s not transparent about how much money will be required, and that might lead to other obligations.

People don’t want to talk to lawyers, but they really want legal strategies and solutions. They are afraid that engaging with a lawyer will be a Pandora’s box, with pricing and timing spinning out of their control. They don’t want to open that box, so instead they try to ‘hack’ legal expertise, by asking friends and family, turning to the Internet, and otherwise trying to scrape together free knowledge.

This theme is in line with some other curious tensions with lay people’s user experiences with the legal system. Another one that I’ve observed is the tension between lay people and lawyers. Both think the other is too transactional, and doesn’t understand the needs and pressures of the other side. They both think the other is overly concerned with money and control, and do not understand what they are going through.

A huge tension, that is reflected in the many above observations, is that lay people can’t find reliable metrics for traditional legal services. There is no clear review system or Angie’s List for lawyers. This pushes people away from hiring lawyers in a traditional way. Rather, they use legal products they can find that resemble other online services that they’re familiar with in other domains, and they use this non-traditional service. For example, they’ll get a will from Legal Zoom, a contract from Docracy, because these sites remind them of other online services that they’ve used without issue. The format of the service leads to trust, in the absence of any reliable metric.

One more tension I’ve observed is the challenge of long-term engagement in getting to legal resolutions. It can be easy to get people to start thinking about getting a legal problem solved (like making a life plan), but it is very difficult to get them to follow through all the way to completion. People opt-out when they have to have difficult conversations, make hard trade-offs, or deal with complex tasks. Even if they started out with best intentions, actually getting through the entire stream of legal tasks to resolve an issue is a long, demanding marathon. They need all kinds of support and incentives to stay engaged and finish things.

A final tension is the lack of prominent legal brands. People don’t know who to trust to help them with legal issues. Perhaps there is a lawyer in their market who has advertised heavily, with slogans, jingles, and other sticky branding. Even then, most people hesitate to trust a lawyer they’ve encountered through advertisements. They seem to crave a more corporate brand, that’s more national, used and trusted by many, that seems to be a ‘standard’. They are looking for a Target, a Costco, or even a WebMD — something that they know many people use successfully.

Tap into user-provided analogies for legal services

Another category of user insights are the analogies that people use when speaking about legal challenges. These metaphors can guide us in figuring out what’s going wrong with current legal services, and then devising better ones.

Especially since people find legal tasks so daunting (if not altogether distasteful), framing them in a more familiar way can be a powerful engagement strategy.

These analogies for legal tasks can be called upon explicitly, or more subtly — by borrowing their tone and brands, patterns of interactions, interface details, or language to describe things. Even if they are to painful or uncomfortable situations, they are often more familiar to users than legal tasks are. This familiarity can help users make sense of what this legal challenge will be like

Here are some of the common metaphors that we’ve encountered from users during our user research and our design workshops. These metaphors are from different types of challenges — everything from planning wills, to creating contracts, to dealing with plea bargain offers, to figuring out divorce and custody processes.

To me, this legal challenge is like…

- Pregnancy, getting prepped for having a baby & going through the pregnancy process. I don’t know exactly what to expect, I’ve only heard pop culture versions of it. I don’t want to screw it up. I want guides, reminders, diagrams, and best practices of what a good expectant parent should be doing.

- Going to the dentist, getting crowns & dental work done. It’s painful. I hate going. I know I need to — the consequences have already started affecting me, and I don’t want the situation to get any worse. But the bill keeps growing. When I walk into the office, I don’t know what the bill is going to be. I don’t understand why all these things are necessary, and so expensive. I’m not sure who to trust. And I’m in pain to top it off. I just want this to be over.

- A Home renovation, in which I’ve hired construction workers and an architect. I have a vision, but I want them to supplement it. I know it could go off the rails, and turn into something way too expensive and perhaps never totally resolved. I’m wary but excited. I want to get this done, I want to work with them, and I want to trust them (but I’m not sure I totally do).

- Planning my Personal Finances, why isn’t there a magazine for legal issues? I want some basic articles to get me grounded. I want a call-in talk show that I can ask questions and get free expert responses. I want homework from trusted experts to get me up to speed so I’m smart about this, just like I’ve gotten smart about saving for retirement.

- Going to an Auto Mechanic. Why isn’t there a Yelp for people to help me? I want to know others’ experiences before I trust my situation to someone, who may not know this specific area very well, or who may try to cheat me. I want to delegate this to an expert, and I want to go to the person who has five stars and 1000 reviews.

- Starbucks, or Costco. I wish legal services were more like this. That my options and prices were all laid out for me to see, so I can compare and choose what best suits me. Also, I can see what the people are doing — it’s clear what is going on and what I’m getting. If I don’t like it, I can return it. They know me by name, there is nice music, they move quickly — I like going there, even if I do end up spending more money than I should.

Core Types of Legal Users

Having spoken about legal users at a general level so far, it is worth diving into some of the main differences of people’s interactions with the legal system.

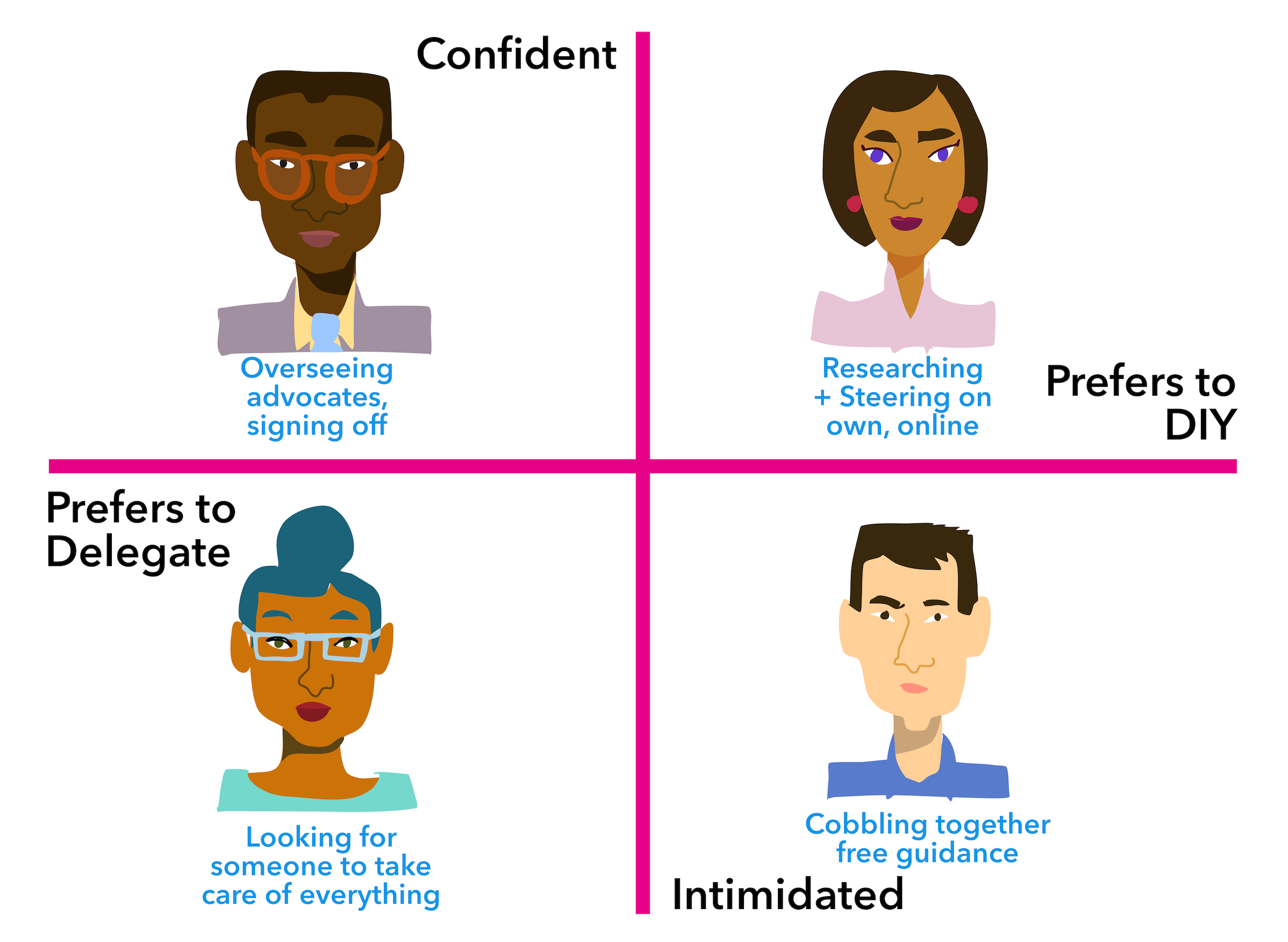

There are two main vectors that we find to divide types of lay people who are interacting with the legal system. First is around confidence vs. intimidation. This can be in regards to technology, the language of law, or of using a complex system. Confidence around these three factors tends to be interlinked.

The other vector is around the desire to take care of tasks yourself versus hand them off to someone else. Irregardless of confidence in one’s ability to navigate the system, some people would rather have another ‘advocate’ take care of their legal tasks and progress. Others want to be the one in charge (and perhaps handing off some tasks), and doing as much of the work on their own.

In our design work, we try to either focus on one of these types of users when we are scoping a project, so that we know how much information we should show, how much of the legal work we should expect the user wants to take charge of, and how much tech to involve.

Diving into specific personas

This matrix view of user types is a helpful first view, but most actual users are hybrids of these — or can hop over the various dividing lines. The generalized persona types, though, can be helpful for a design team, as they’re thinking of how to make a solution work for many different types of users.

To that end, I dive into some more detailed views of the user-types in the matrix above, as well as some people who are in-between the clear categories.

These archetypes are generalizations that help us segment our potential user types, based on how people prefer to consume and use information, and what kind of frames will resonate with them.

The Do-It-Yourself, Confident User Type

The DIY user is confident in her ability to read and comprehend information, even complex legal information. She just wants to get her task done and move on with her life. She realizes that a lawyer may help her out, but she feels that might be a waste of time or more trouble than it’s worth.

She is Internet-savvy and figures that she can Google the guidance, definitions, and strategies that she might need to use to get the legal task done. She is ready to plow ahead and try her hand at doing the legal work herself.

The DIY user thinks, “I’m smart & capable, I’m going to try to get as much of this done as possible. I’ve seen the television shows. I’ve Googled the topics. I can figure out what I’m doing. Maybe I’ll ask for help on somethings, but I’d rather do it on my own, and with Internet forum help, rather than pay a high priced expert.”

The Cautious-Traditionalist User Type

The Cautious-Traditionalist user is eager to hand off her situation to an expert as quickly as possible. She doesn’t trust in her own ability to do things right, or expects the system to be so complicated that she cannot trust her own intelligence, gut, and research skills to serve her well enough. She would rather rely on someone who specializes in law to make her decisions for her.

We also have termed this user type as The Traditionalist. This person wants a hierarchical relationship, in which there is a total hand-off. Me Client, You Lawyer. Never the twain shall meet — take my problem, go solve it, and I’ll pay.

Looking For Father user type

The Looking For Father user wants a trusted authority, like a parent or a friend with experience, to be an adviser as she starts to figure out what to do. She might start searching around the Internet, her social networks, or face-to-face conversations to help her understand her problem.

What she wants is to find a person she knows, whom she expects to have some life experience in this area, to ask what they would do. Ideally, she can get this person to give her a gameplan or specific references. It doesn’t even need to be a lawyer.

The Strategist/Co-Pilot user type

A less common user is the one who’s invested in being a smart-shopping, strategic co-pilot. This user type wants to find a lawyer (and not take the DIY route) but who also goes into the relationship attuned to how to be in control of the relationship. This user type will shop around and gather metrics about possible lawyers, strategies, and paths of action. They will hire a lawyer, but don’t trust them enough to know what’s best.

This user type tends to play the lawyer role themselves, though they don’t trust themselves fully to do their tasks DIY. In their point of view, they think, “I want my legal problem taken care of in total, I want to be the best prepared person on the block, I go to a bunch of different lawyers to find the one that will fit, and even then I want a second & third opinion about the quality of the service/document that I received.”

In their co-pilot stance, they want to know what their lawyer is doing, and how the process works. They’re willing to do homework to keep up with (or even surpass) their advocates and experts. They want to be in the cockpit making decisions.

The Speeding Executive user type

Another less-common user-type is the person who is speeding through tasks and prioritizes efficiency. They value their own intelligence and ability to make gut decisions. They want enough information from a product, service, or person to get a basic understanding of the terrain, and their options. They want this thing to help facilitate their decision.

In their voice, this user thinks, “Just tell me what I need to know, give me the facts & the rundown, have it already processed. Then and only then let me make the essential choice before I hand it back over to you.”

How to deal with different User Types

Realizing that legal services should serve all types of people,the question becomes how to create a new thing that works for these many different user types?

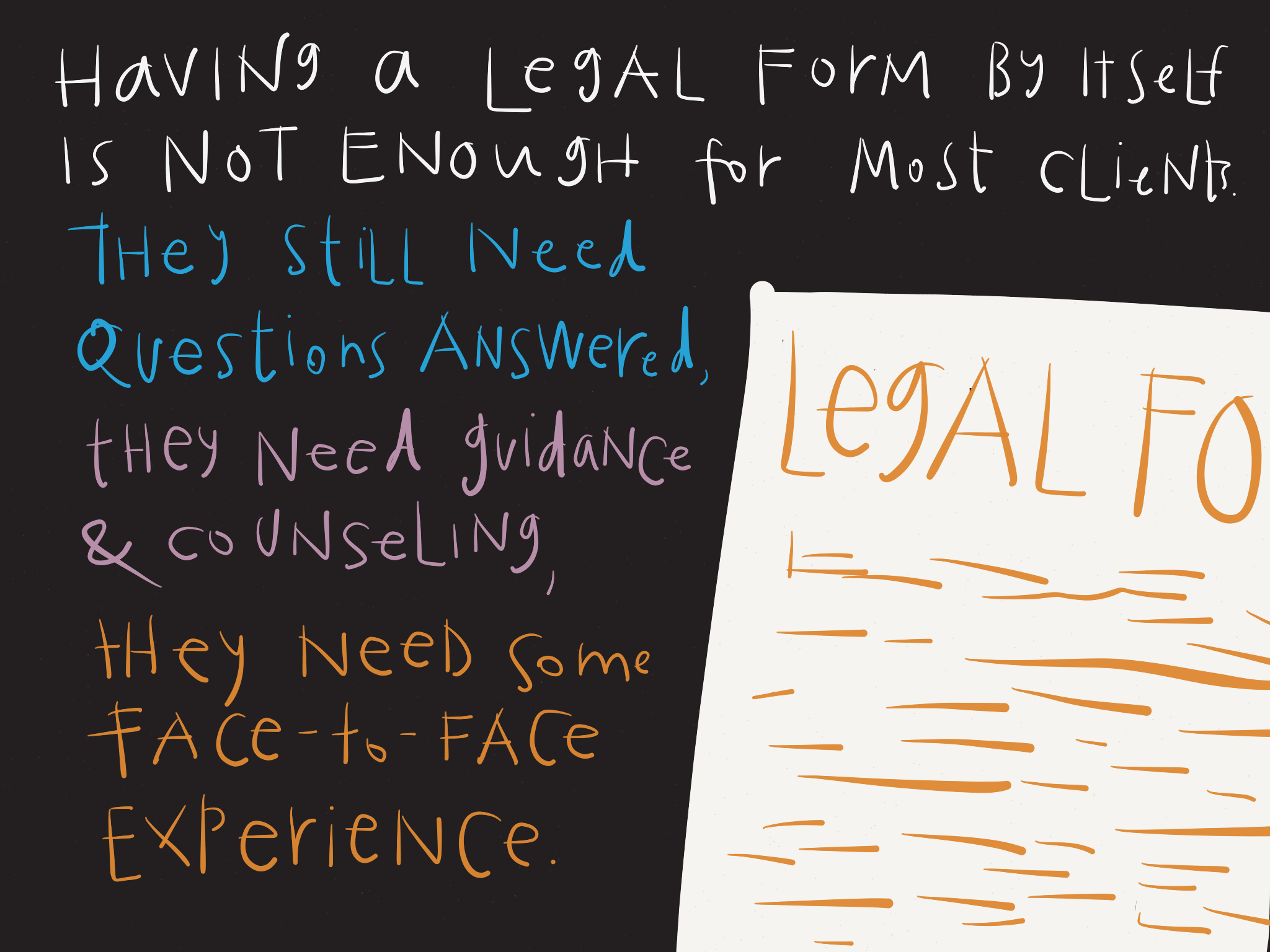

Provide multi-modal services, that the various types can adjust to meet their particular preferences. Some can be DIY, self-serve, low-touch, tech-enabled services that more ambitious people can do themselves, along with high-touch, in-person services from legal experts for people who are more reluctant to do legal work on their own or for tasks that are too difficult. There can also be a middle-ground type of service, in which a layperson is assisted in a medium-touch way by some kind of legal expert — a non-lawyer navigator, an artificial intelligence-powered expert system, or a lawyer.

Create multi-entry, multi-framed types of services, that will resonate with many different kinds of user types. For example, combine human-to-human interactions on one track (for high-touch users), with human-to-tech interactions on another (for DIY types). Either by itself will leave a significant population under-served.

And even for DIY types, they may want to switch lanes at some points. They may end up facing language, decisions, or tasks that they don’t feel competent to deal with. In those instances, your service needs to supplement the human-to-tech interaction. A good legal design will allow users to switch lanes, getting unbundled instances of help on, for instance, filling out a form. Then the user may want to go back to filling it out themselves, after they’ve gotten a little guidance.

The Different Legal Design Use Cases

Aside from the different types of people who use the legal system, there are distinct kinds of legal tasks — each of which carries its own kind of design requirements. What kinds of problems do people have, that they need new legal products and services?

These are the use cases, that are common patterns of the types of problems, goals, and contexts that we’ve observed people in, when they need new kinds of legal solutions.

The following outlines of Use Cases can be useful to a design team as a point of inspiration. Each of these use cases can be morphed into a design brief, to help a person do this task better.

They can also be a review mechanism for people working in the legal system now. What task are you helping your users achieve? Do you know your use cases?

Lay People Use Cases with the Law

Most of my design work has focused on helping people without legal training through the legal system. The following are the most prominent categories of challenges that lay people have, that are motivating them to use the law.

- Getting a Benefit. I am trying to get a benefit from the government — a pay out, an immigration status, food stamps (something they don’t need to give me, but I want them to give me, that I will get benefit from)

- Fulfilling a Civic Obligation. I am fulfilling an obligation to the government — pay my taxes, do jury duty (something they require me to do, but that I don’t necessarily want to do, that I’m afraid of getting a penalty)

- Avoiding a Penalty for Bad Behavior. I am accused of breaking a government rule. I am trying to protect myself from a possible punishment.

- Settling a Private Dispute. I have a problem with another private party (an individual, a company, or otherwise). I want to make a claim against them — to get them to change their behavior, give me monetary compensation, or otherwise ‘make me whole’.

- Future-proofing. I want to make a plan for a future scenario that might arise, and make this plan binding so that it will protect my interests. For example, I want to make a will that will ensure my assets are distributed as I wish them to be. Or I want to craft a contract with another party to make we behave as intended.

- Protecting myself from another. A private party is trying to take something away from me. I want to stop them and protect myself. For example, I want to protect myself from an eviction, or from a lawsuit.

Legal Professional Use Cases

It’s not just lay people who need legal products and services. Lawyers, paralegals, judges, court administrators, and other legal professionals also need well-designed support. Here are some of the most prominent legal use cases we’ve observed for the professional.

- Packaging Knowledge. I want to give my clients and my fellow lawyers more insightful, user-friendly tools to know what the law says on matters I’ve already researched — as well as who they should be working with and how to work with them.

- Professional Development. I want to train other lawyers in my organization to work better, and to manage their teams, their client relationships, and themselves in better ways.

- Change Management. I want to figure out how to get the people I work with to be more collaborative, more experimental, and more invested in the long-term of the organization.

- Communication Skills. I want to communicate rules, arguments, and stories to non-lawyers so that they can understand them.

- Efficiency Boost. I want to be more efficient in delivering high quality work. For example, I want to work with more efficiency, better relationships to clients, and more value and revenue created.

- Harnessing Tech, Automation, and AI. I want to be able to take care of straightforward stuff more easily and then have more time to work on the complicated, bespoke matters.

Opportunities for Legal Design Work

Taking a step back from these two sets of use cases, we can begin to see some product types emerge. Reframing these use-cases as potential product categories, here are zones for new legal design and technology work.

- Assist in the Creation and Enforcement of Contracts: I want to make a binding agreement

- Help Private Parties Resolve Disputes: I want to resolve a dispute

- Support Professionals to Manage Cases: I want to manage my cases and work inside my legal organization

- Triage and Diagnose Lay People: I want to figure out what my issues are, and what legal categories I’m in

- Guide a Lay Person through Legal Planning: I want create a legal plan through a document

- Know Your Rights: I want to understand what my rights are vis-a-vis the government or other

- Make a claim: Try to recover money or prevent a money penalty against you, by using a service to represent your story

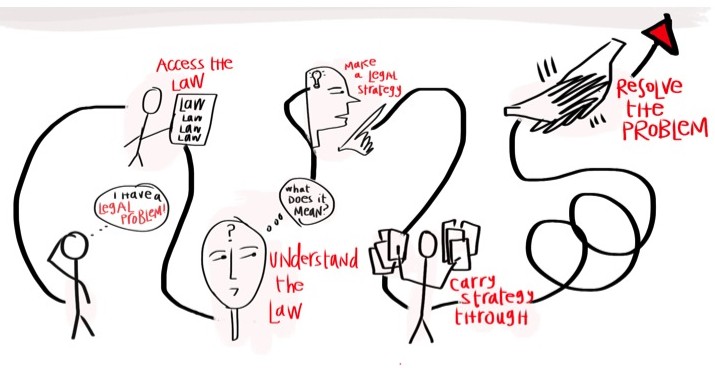

Know which part of the legal journey your product/service is focused upon, and focus on understanding users’ needs at that specific touchpoint — while also helping them in the before & the after to this touchpoint. Construct your design to effectively receive them from their previous stage, help them get through this target area, and then send them off to the next stage so that they’re prepared for it.

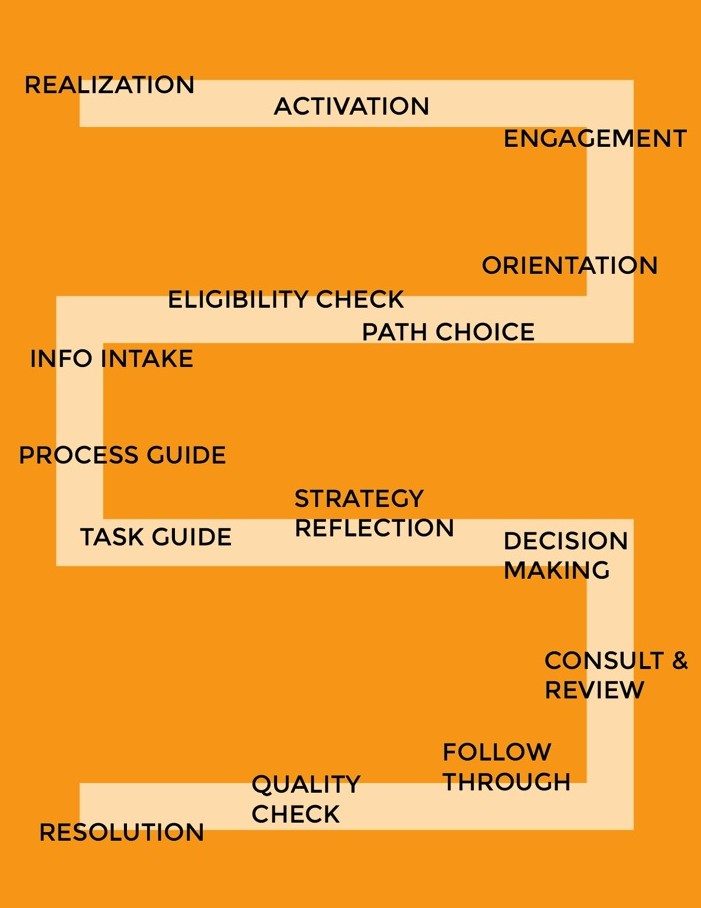

When we think of the legal system through the lens of the model Legal User Journey — mapping out the steps from beginning to end that an archetypal person would take to move through an archetypal legal process.

This modeled process identifies the opportunity areas for where we can be building new products, and offering more value. Mapping out the model Legal User Journey also helps us see how we can integrate trust, routines, other touch points to find opportunity areas to help people flow easily through the legal system.

These journey maps reveal Patterns & Types. What are the common challenges, tasks, and outcomes that go into a legal service? Using the journey framework, we can use them to be more systematic, intentional, and knowledgeable about what kind of innovation we’re creating, and how best to do so.

From the modeled User Journey, I have created a shortlist of key Legal Patterns. These are the main types of legal functions and experiences that we can be designing for. The Legal Pattern Library gives a range of models and patterns for the essential functions of legal products and services. You can see a working copy here at this other site — I will be adding more detail into the book in future months.

The pattern library is meant to inspire and guide your work.

- React against bad design that you think will not work for your own product.

- Borrow from good design that you find usable and engaging.

- Do not copy directly, but use these examples as templates and provocations.

The Pattern Library these core consumer law product types, and then gives examples and insights into how to best create them. The pattern groups are as follows:

- Orientation and Education Tools

- Engagement and Activation Tools

- Triage and Diagnosis Tools

- Exploratory, Strategy-Maker, Decision-Maker Tools

- Follow-Through, Process Guide Tools

- Resolution and Maintenance Tools

- Assessment and Review Tools

For those trying to serve people accessing legal services — whether with the courts, private lawyers, legal aid, or non-lawyer providers — there are certain camps of tools that these people need. These patterns can help us think more discretely about what the given problem is, who else has thought about it, and where we can intervene.

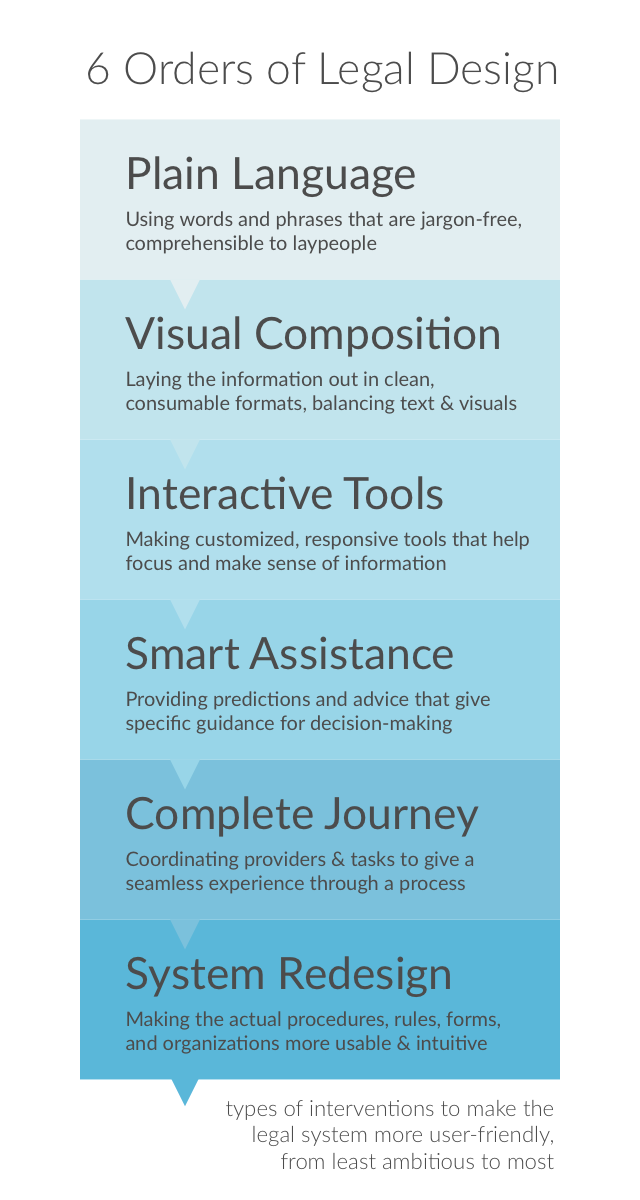

Six Orders of Legal Design Interventions

From all of this detail about users, patterns, and principles, let me return to the big question: How can we make the legal system better?

I posit that there are six main orders of Legal Design Interventions. By order, I mean a type of thing we can create in response to resolve users’ requirements and take advantage of the product opportunities outlined above. All of the earlier design mechanics outline principles and opportunities for making the legal system more user-friendly. These six orders point to the types of things we can actually craft and bring into the legal system to transform it for the sake of its users.

They all may improve the user experience of the legal system, but they range in how ambitious they are and how much effect they can have.

Here are the 6 orders, from least ambitious to most.

11 replies on “4: Legal Design Mechanics”

Margaret – I just discovered this site. This is amazing! It is needed and I want to help!

Hi Margaret, congratulations and thanks for the precious material and insights!

Is there any way to contact you? Do you offer legal design services?

Hi Margaret,

I wanto to learn how to create legal visualization. Do you have any suggestion?

Many thanks

Micol

Super

Hi Margaret,

Thanks for sharing this incredible material. I am working on the interaction of legal design and the GDPR transparency principle and your book is very useful.

Thank you Margaret. your essay introduces lay people into new world where each lawyer can change his own mindset, realize new model of relationship in the legal world and solve many gaps between client and him self. if you come in italy I wish I could meet you

Hi there! The Legal Pattern Library does not seem to be accessible. Is there any way I can access that tool for my students to play around with? Thank you – this is marvelous !

Adorei o conteúdo! Vocês possuem curso?

Hi, I found it very useful as a great resource to create specific legal designs for specific users. Thank you.

Thank you!