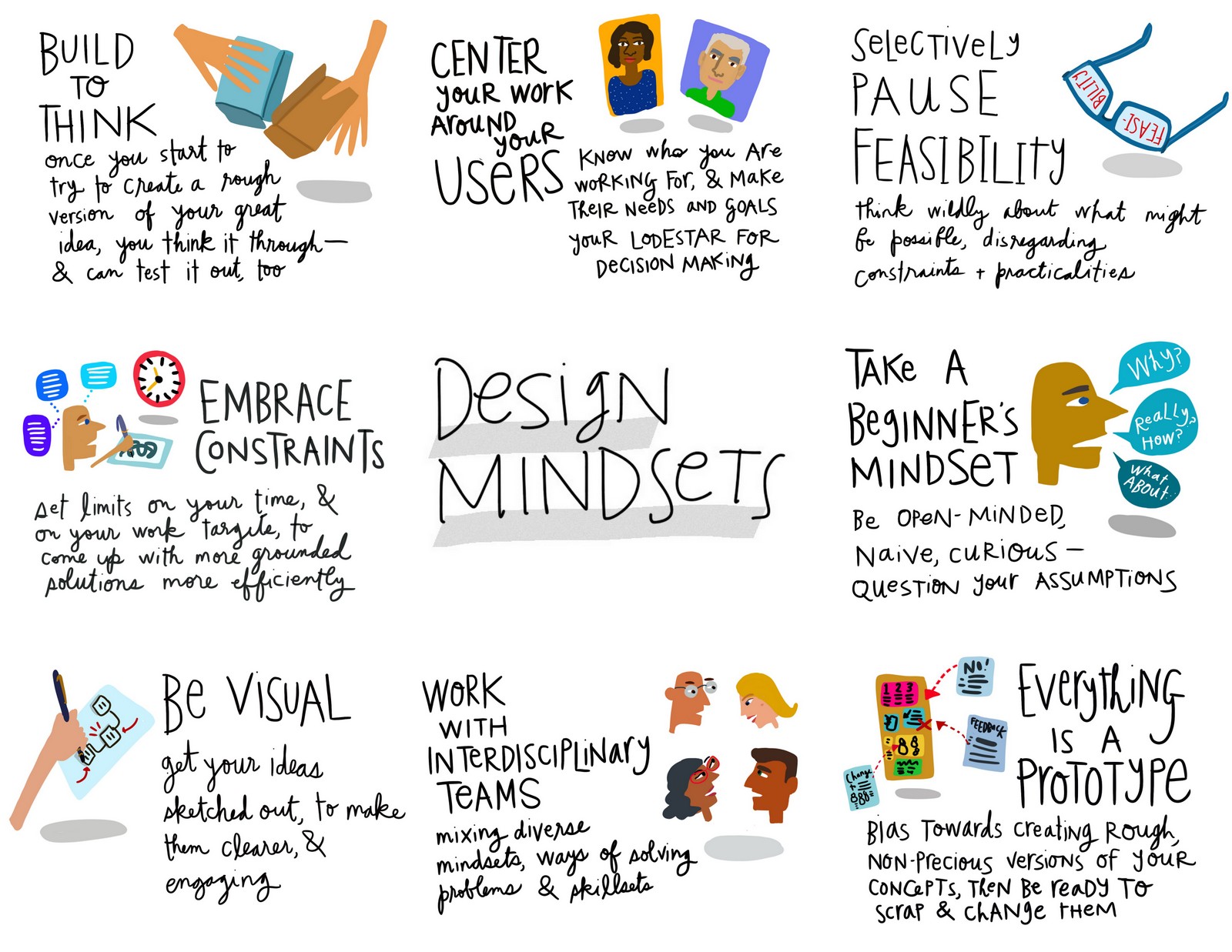

Design Mindsets are the lenses that we wear to be more creative, user-centered, and agile.

To take a design approach, one of the key shifts for lawyers is to embrace new mindsets. The approach brings fresh lenses with which to see our work, our challenges, and our resources. The mindsets of a designer diverge from those of a traditional lawyer. Adopting these new perspectives can be painful but revelatory for those interested in improving the legal system.

Design mindsets are about how we can work, and how we can tackle problems. Below, find sketch I made of the many ways of thinking that I learned while at Stanford’s d.school. Most were awkward and uncomfortable to me after so many years in academia & then law school. These don’t come naturally to all lawyers, but with practice (and culture-change) they are easy to learn.

Boiling down these many approaches, I focus here on a handful of core mindsets that can be most transformative for lawyers. This chapter presents them in detail. At an even more fundamental level, legal design is grounded in three fundamental principles.

- Be user-centered. Do things and provide things that your intended audience can use, that are useful to them, and that they want to use.

- Be experimental. Open yourself to new ways of doing things, and trying them in quick and thoughtful ways to see if they work.

- Be intentional in how you operate. Be conscious of what kind of process you are using, what space you’re in, what might be going wrong, and what might be made better. Be ready to change and adapt to make for better outcomes.

These three principles can be your lodestars as you navigate the design process to create something new, innovative, and successful.

The Core Mindsets

That said, it’s worthwhile to dive into the particular mindsets that designers bring to their work. These core mindsets can frame, inspire, and guide your approach to your work.

They can be adapted into legal professionals’ work, at a modest level or a more ambitious one. If you are an entrepreneur or an innovator, they can help you find breakthrough new concepts and get you quickly to a new offering. Or, even if you’re not creating something ‘innovative’, you can use them to make improvements to how you work and how you connect to your users.

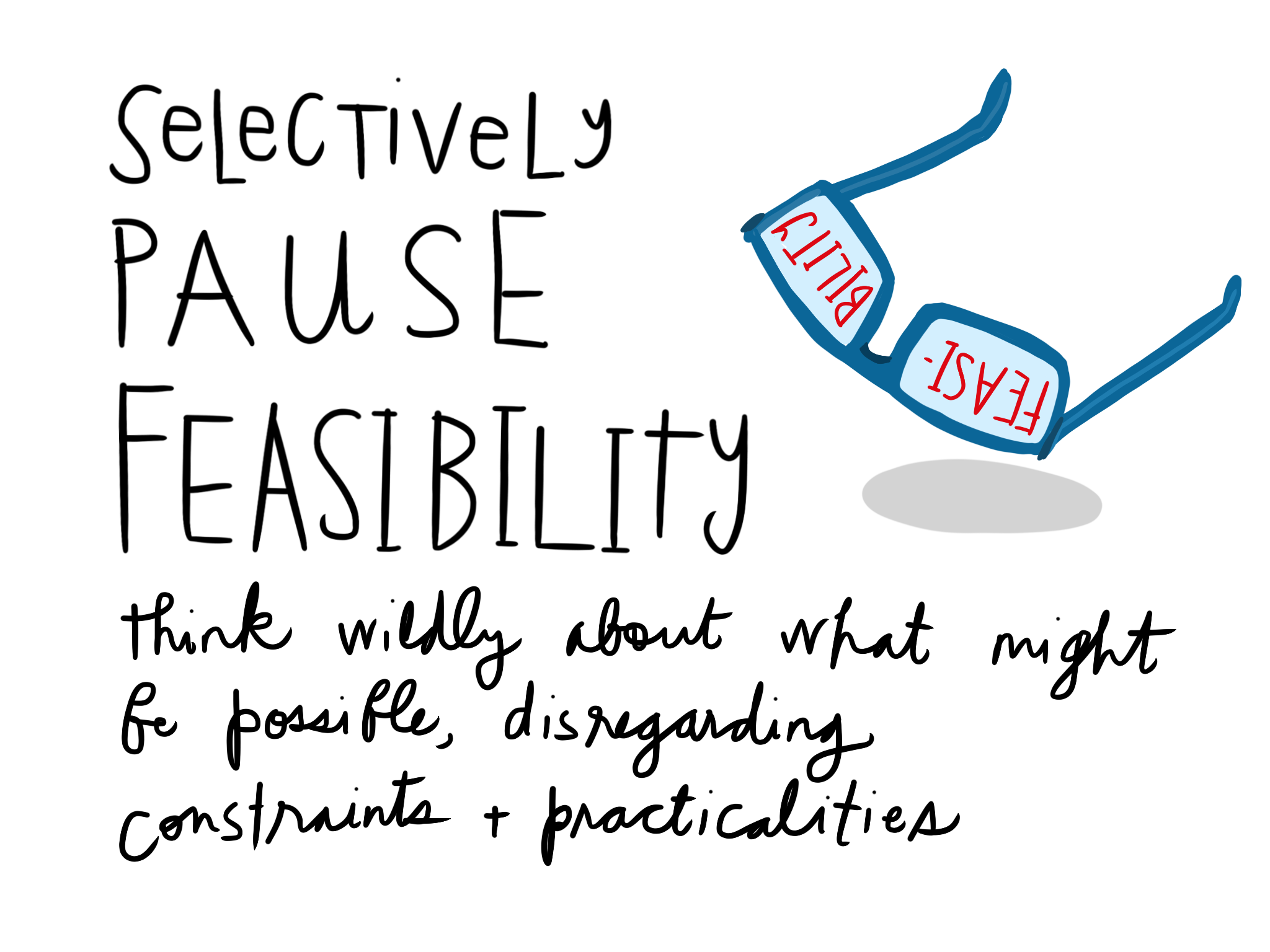

Pausing Feasibility

Perhaps the most powerful design mindset that lawyers can adopt is to Pause Feasibility. It is one of the most uncomfortable for lawyers.

Even if it is just for five minutes: take away all the constraints of budgets, regulations, organizational pressures, and other limits that you operate within.

Now, with these sidelined: What would be a better way of doing things? What would be an ideal, unbelievable, headline-grabbing version of what could be in our legal system?

The Pause Feasibility mindset allows new ideas for innovation to bubble up — and possibly also to move forward. Rather than let feasibility critiques cut off ideas before they can be tried, the goal is to let the crazy and impossible ideas float around, see if they can be made viable (or the system could be changed to make them so).

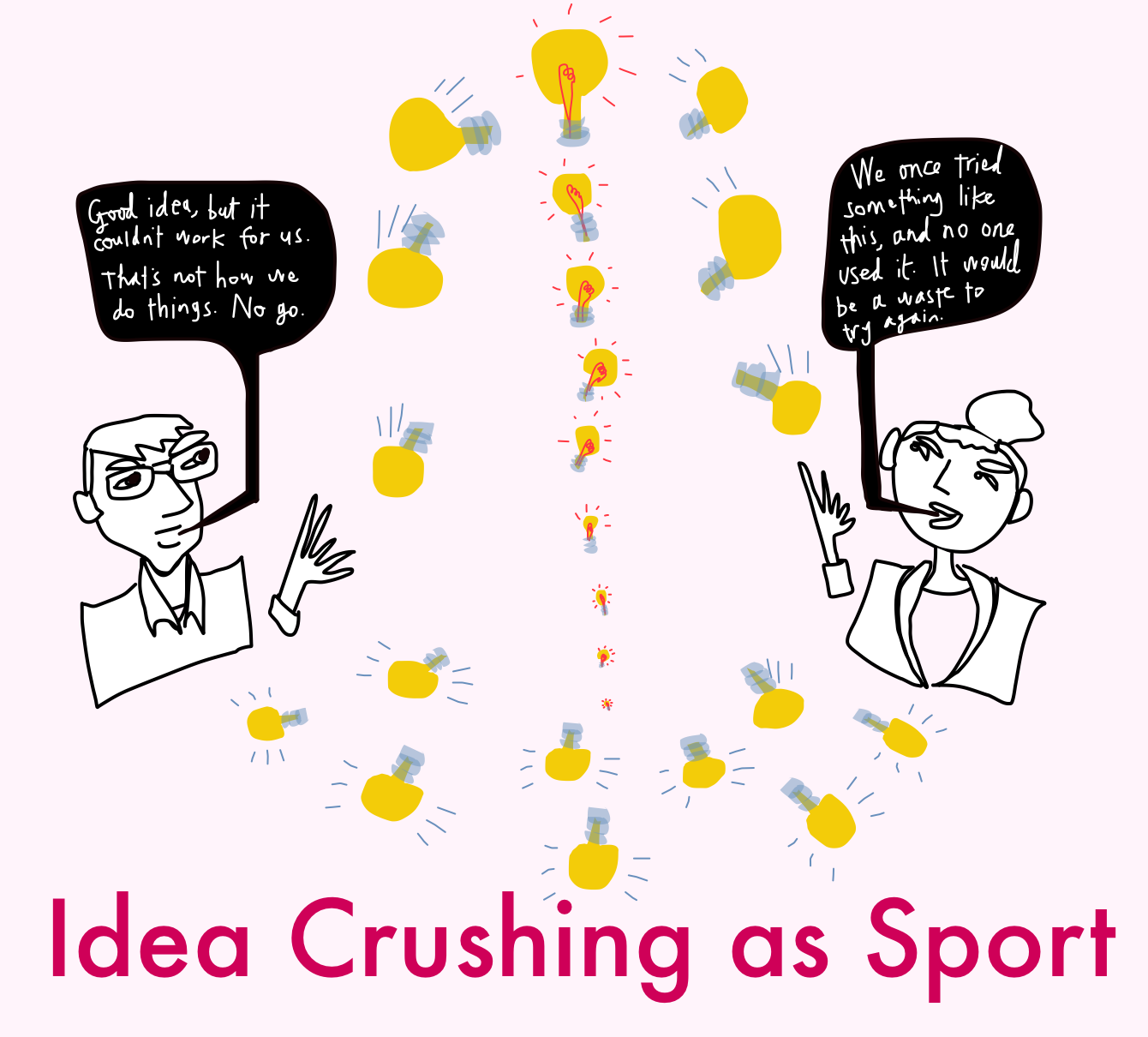

Though lawyers tend to make a sport out of shooting down ideas as quickly and thoroughly as possible — whether it’s because ‘they’ve been tried before,’ an instinct says that ‘it won’t work’, or otherwise. But the designer’s mindset pushes us to explore and test ambitious ideas before trashing them. Even if it would be against the law, be over-budget, or be complex (or impossible) to make, it’s worth spending some time ruminating on big, risky, wild ideas.

These massive or magical concepts can stretch your thinking and broaden the scale of your ambitions. The big ideas can be put onto a future agenda, scaled down to a more affordable version, or edited into something less extreme. They can also make you more aware of the systemic constraints in which you operate — and help you understand which of these you might want to aim at.

We’ve been trained as lawyers to poke holes and give critiques, but often that stops us from creating new things or supporting others who are doing so. Critiques are necessary and essential to the design process (see below), but they should be used at certain times of the process, while reserving other times as critique-free. If we can pause feasibility temporarily, we give new ideas some breathing room to see if they’re worth incubating further.

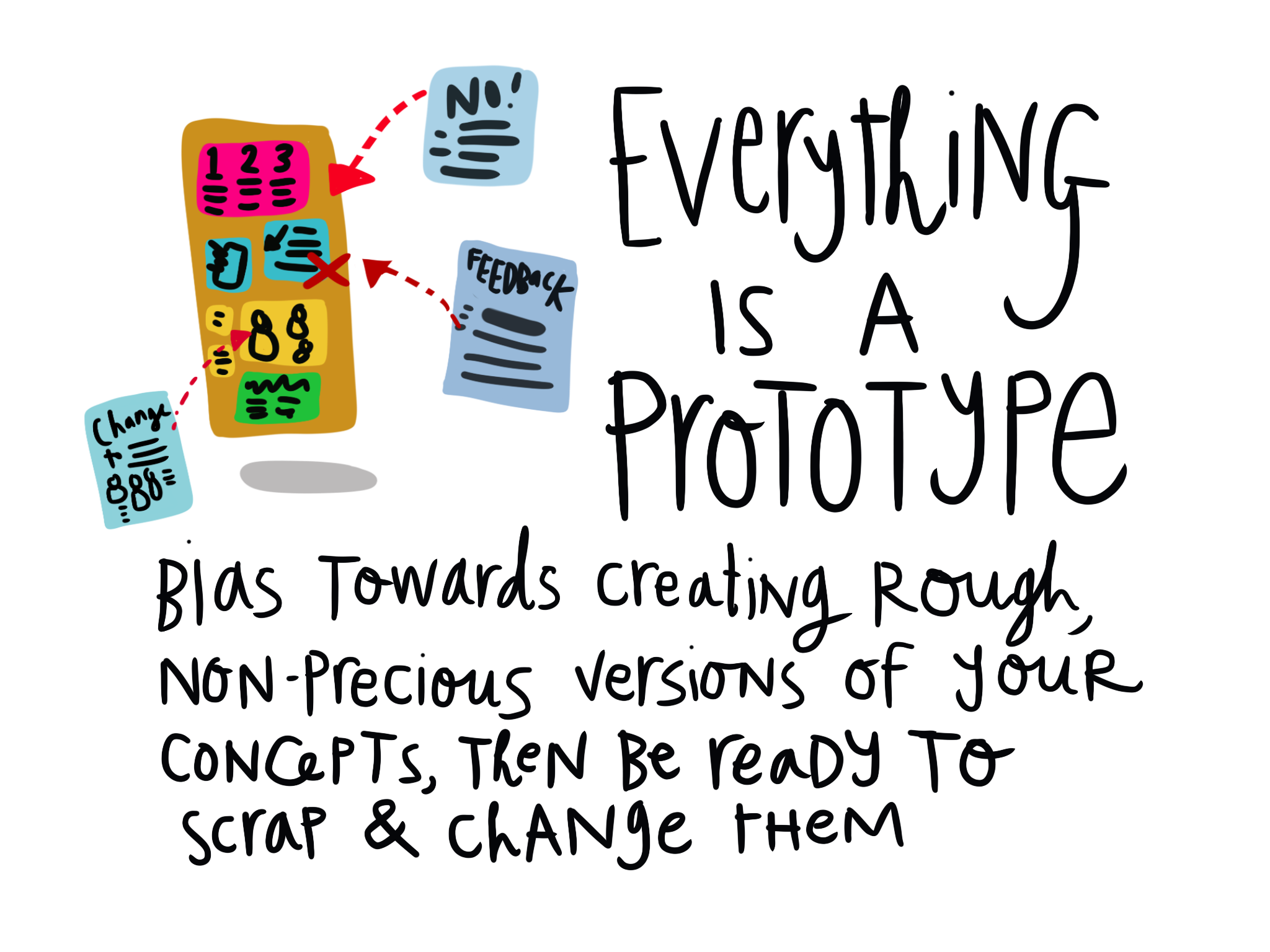

Everything is a Prototype

My favorite design mindset is that Everything is a Prototype.

Designers work in quick cycles of Have a Promising Idea -> Build It -> Get Feedback -> Iterate or Abandon. This is a prototype-driven way of working, and of seeing your own creation. It means working in loops rather than a straight line.

Instead of holding onto one great idea, and working to perfect it before releasing it to an audience — this mindset means exposing your ‘great idea’ early on to feedback, even before it’s completely developed (the earlier the better). This feedback, especially in more critical forms, can guide you to a more viable version of your idea. Or it can help you to abandon a bad idea altogether.

Be Quick to Build, Quick to Test, and ready to scrap what doesn’t work as you keep iterating. If you think of everything you do as a prototype rather than as something that must be perfect, you can act more creatively and tap into others’ creativity and expertise.

[visual on quick and agile, embrace failure]

Developing ideas in a loop rather than a line may seem to be inefficient, but it stops you from wasting your time, effort, and money on ideas that aren’t worth developing. Building and testing quick prototypes of a concept will quickly tell you its worth.

It will also save you from falling too in love with ideas that you’ve dreamed up, but haven’t figured out if they’re workable. When you develop ideas in a linear fashion, you often become over-invested in their success and cannot acknowledge criticisms or failures, for fear that all your work was wasted. You also lose your own critical perspective, and start believing this solution is the only worthwhile one.

Making radically-scaled down prototypes of products (or even of complex systems and services) can give valuable data about whether to pursue or scrap them. Embrace early failure, rather than getting destroyed by it later.

Welcome, Criticism

To say it again explicitly: Welcoming Criticism is essential. But it’s tough to practice, especially for those of us inclined towards Type-A perfectionism. It has enormous benefit the quality of your work and its value for the end-user, though, when you can build up resilience to criticisms. It may hurt to hear your work is unattractive, unhelpful, confusing, dysfunctional, or otherwise lacking.

The goal of your efforts shouldn’t be your own ego. It’s about how you can make things better, and this criticism will give the direction about how to do that.

It’s tempting to avoid reading the one-star reviews or talking to clients who are unhappy, but this is where you can fix your current offerings and identify the best ways to develop something new. Criticisms are your agenda of what to work on.

Lawyers Becoming Feedback-driven & Iterative

Taking on criticism and showing our non-perfect first drafts are intimidating tasks for lawyers. But the more feedback we can gather on the things we create, the better we can make future versions. It is about letting go the veneer of instant perfection and all-knowing expertise, and working in build-test-refine stages.

That doesn’t mean delivering important work product to the final client as a half-baked prototype. Rather, it means before that final deadline for a brief, a presentation, or a memo comes due, you have gone through several rounds of making rough first versions, getting others’ eyes on them to get their thoughts and advice, and you’ve selectively parsed out that feedback to make a better final deliverable.

It also means making time for debrief sessions regularly at your work, so that your team can express feedback to each other regularly and comfortably. And doing so with clients as well — scheduling post-mortems to evaluate what could have been done better, holding usability tests of possible new products or services, any way to get more of your users’ voice integrated into future work.

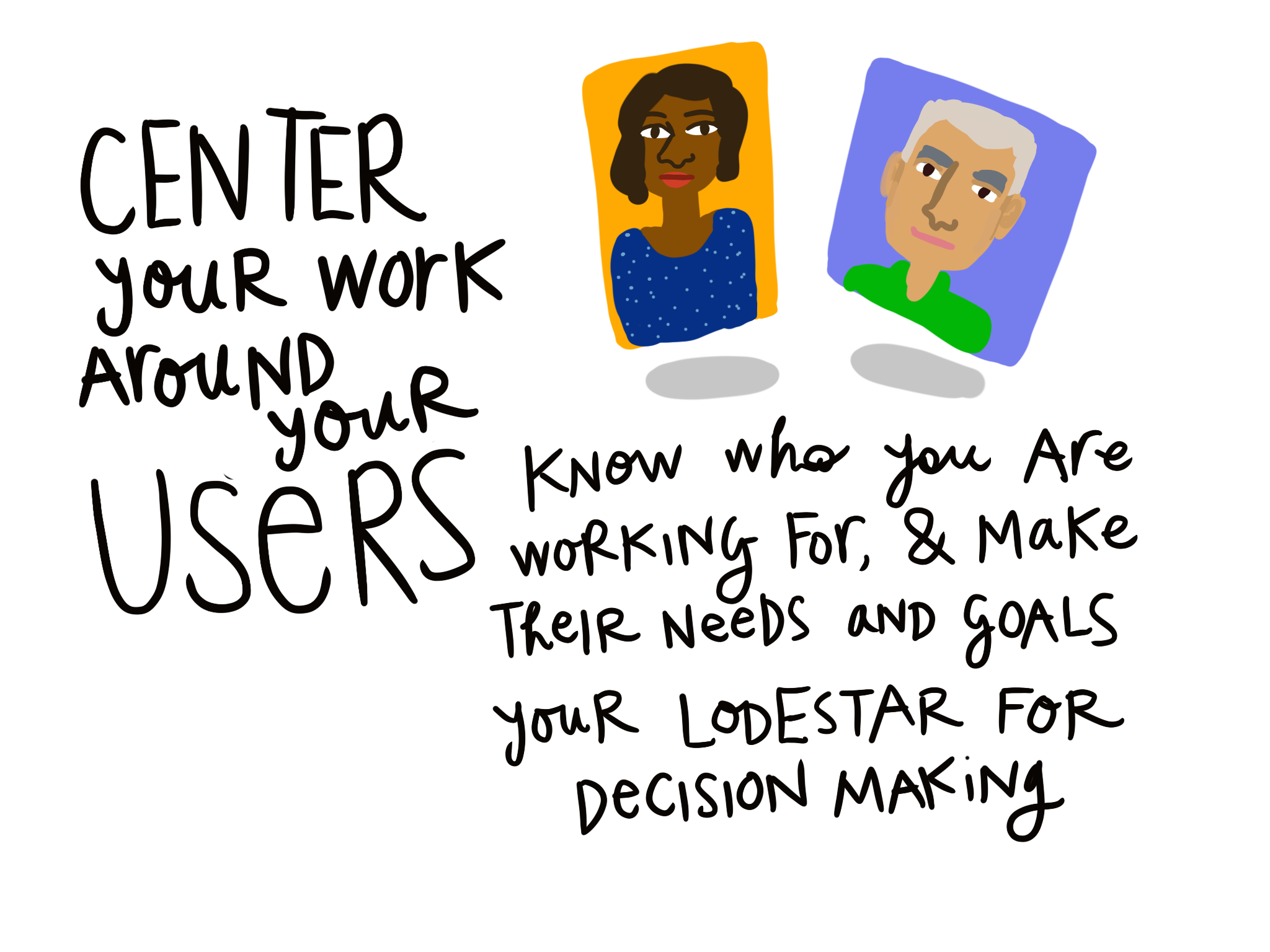

Users at the Center

Another core design mindset: Being User-Centered.

Who is the user? It is the person for whom your service is meant to serve. It’s the person you want to use your product. It’s the person who’s trying to make their way through your system.

There are many types of users in any of these groups, so it’s tempting to think of them in abstractions — as faceless people that you think you can intuitively understand. It seems easier to make educated guesses about what your users want and need, like if you are smart enough you can figure out what would be best for them.

A design approach counters this notion, though. You should scout out specific target users, talk to them, watch how they behave, and listen to their backstories. Investing in understanding your users may seem like a luxury.

Why run focus groups, surveys, or interviews, when you could make educated guesses about what people want and how they’ll react to your ideas? But involving users directly in your design process will give you priceless data about what your target audience needs and how best to deliver it to them.

Being user-centered means Being Participatory, looping in stakeholders into your process. You can have the people you’re working with join you in trying to create new solutions. Rather than you playing the all-powerful expert who will solve their problems for them, the participatory approach means deferring to your users and other experts at key moments. The users’ voices should drive your work.

How to actually center your work around users? Rather than assume you’re smart enough to predict what their preferences are, talk to them. Consults with users should happen at multiple points — as you’re defining what you’re working on and what problem you’re trying to solve; as you’re coming up with ideas and deciding which to pursue; and as you’re testing out something you’ve made.

But that is not to say that what the user wants and professes will totally define what you develop as a solution. The design process’ priority of focusing on the users’ experience does not mean that the designer should strictly adhere to the users’ preferences to the exclusion of all other possible paths. The designer’s judgment, intuitions, and creative have an important place in the process. The design team should weave together the needs of the users, with its own creative leaps and observations from other situations to find breakthrough designs.

Hold Off on the Perfect Solution

Don’t assume you know what you are trying to solve for, let alone what you are trying to build, until you have explored the challenge area.

I like to start out in a wider geography — a zone of a challenge, with lots of different actors, processes, and dynamics at play. As I do research in these areas, then I begin to narrow down to a specific problem. Before narrowing into exactly how to solve a problem, or even what problem you’re trying to solve, first do research into the ecosystem your challenge is embedded in. You need to stake out your stakeholders’ needs and the system’s failpoints first. Then you can more intelligently frame the problem you’re trying to solve.

This mindset also points to the notion that we should Not Jump to Solutions too soon. This can be hard for bright people who like to solve problems. It’s tempting to rush headlong to the ‘one perfect solution’.

A designer’s mindset says wait. Don’t define the solution until you understand the problem on the ground. Don’t get distracted by new technologies that are trumpeted as the new big thing. Don’t get distracted by your own ego, in the form of a great idea that you’ve had and that you assume will fix a problem.

Follow your users and your context, to see what will give them value and actually work for them.

Get Specific, Go for the Extreme

A complementary mindset to be user-centered is to avoid thinking of users as a generic mass. Instead, choose Specific Archetypes to guide your work. It could be a single person, or a composite of similar types of people. The goal is to think of them not just as a ‘user’ (that is, only as someone who only exists vis-a-vis your work), but as a person who is complex and unique. That means going deep about who they are, and who they aspire to be.

Choosing a specific user (or a handful of them) can prevent you from making an overly-generic design. Your work should be grounded in specific use cases and user stories. Before you start building out your ideas (or even choosing which idea to focus on), a design approach has you give names and stories to your target users.

Often, designers choose ‘extreme users’ to focus on. They build their product to address someone with an extreme problem, an extreme obsession with a thing, an extreme impairment, or is otherwise at the far end of a spectrum. Designing for extremes can result in stronger work, that serves a wider public well (and not just that extreme target user).

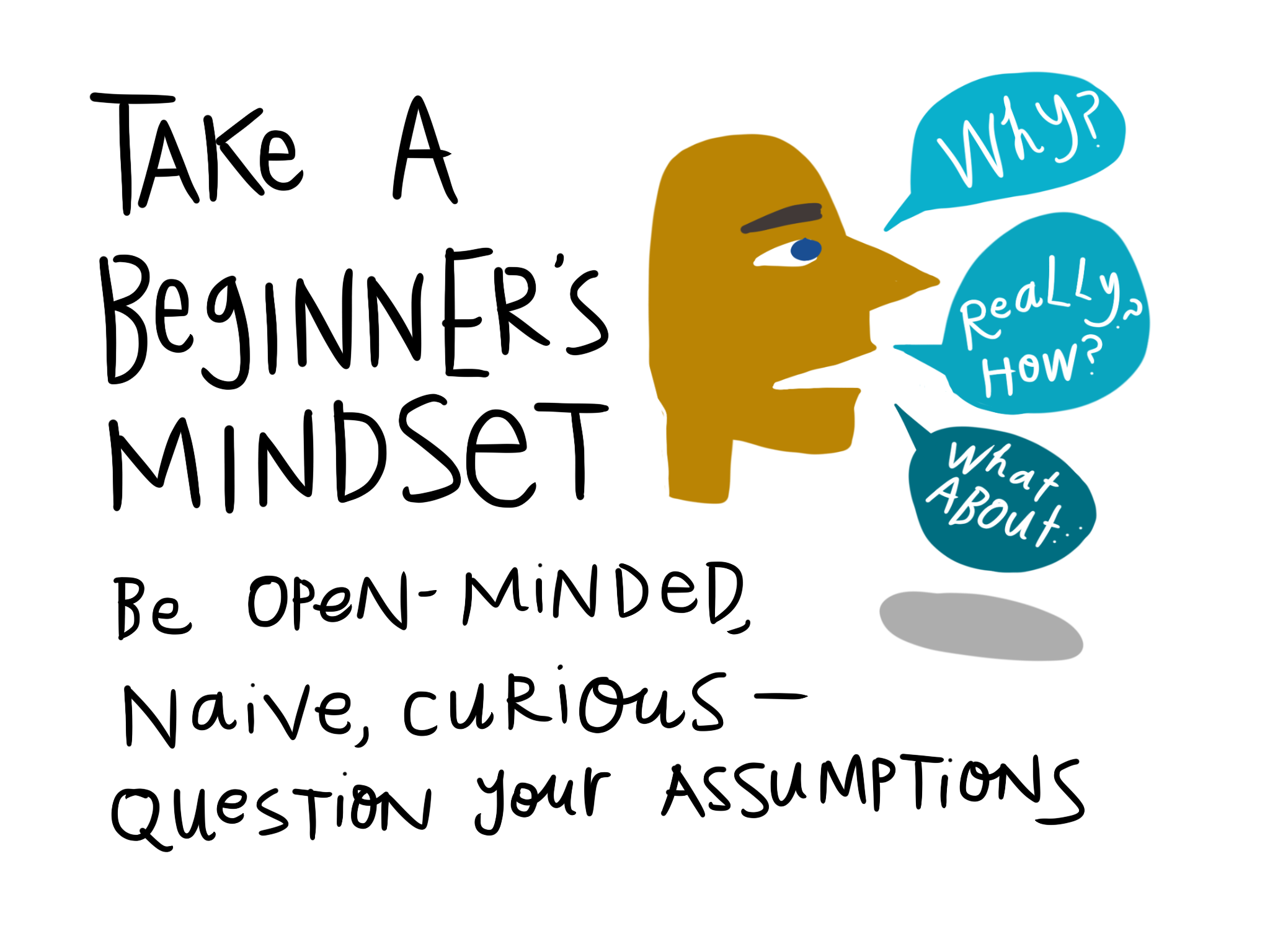

Questioning Everything, Like a Beginner

As you explore your users and the challenge area they’re embedded in, go in with a Beginner’s Mindset. Even if you have expertise in the area, try to take yourself out of the “expert” position and defer to your users and stakeholders as the experts. Be curious, and be open-minded. Don’t automatically categorize what you’re seeing and hearing into your existing framework.

Forced naiveté can help you step away from your mental model and understand their’s.

The attitude of a curious, naive person can help you uncover deeper needs, and richer stories. The key tool of the beginner’s mindset: asking why, and doing so repeatedly. The ‘why’ questions will take your conversations with stakeholders out of the territory of cliched scripts that people tell each other to move conversations along, and into more meaningful stories and explanations of how that person experiences the world.

Using this mindset uncovers Deeper, Less Obvious Needs. It can lead to breakthrough, meaningful new concepts — that will hit needs that people don’t know how to exprsess, and that a more transactional approach would ignore.

Flipping Our Perspective from Lawyer to Layperson

With this mindset, we can begin to see the world again as people who are not lawyers. It is tough to take off the analytic lens that law school and practice has given us. It’s also hard to remember how intimidating, confusing, and dehumanizing the legal system can be to those who don’t know its essentials (that is, most everyone who has not been to law school).

If we can begin to selectively shed our expertise, and play the beginner again — with curiosity, without any assumptions or theories, and by tuning into the needs and stories of the people we’re serving — we can see the legal domain fresh. It will help us scout new opportunities, improve how we work and create work product, and build our connections with others.

Working in a Mixed Team

Interdisciplinary Collaboration is essential to come up with better solutions to problems. Working with people with different domain expertise will mix mental models, ways of solving problems, and knowledge of possible solutions. This way, proven solutions from one field can be adapted into another.

Interdisciplinary work is not always easy. Jargon and ego often get in the way. Some are suspicious of other domains’ research methods or priorities.

But learning to establish common framings of challenges and to exchange ideas for solving them can make design work much richer. An engineer can see the challenge area and solutions in ways that lawyers cannot. A developer may know new technical solutions that lawyers never dreamed of. And a professional designer can envision a better work product, beyond what a lawyer could imagine.

A group of lawyers seated around a boardroom is not going to produce legal innovations like a mix of engineers, designers, educators, doctors, info architects, and lawyers.

Going Visual

Visualizing concepts can be very difficult. Lawyers tend to prefer using words and text to communicate. But the more visual we are, the more we show rather than tell, the more we make rather than describe — the more powerfully we can construct and communicate our ideas.

Being visual like a designer does not mean creating perfect works of art. Rather, it’s a commitment to using sketches, diagrams, human figures, and other visual representations to ground what you’re saying.

How to get started on being visual? Sketch what you’re trying to say. Draw out your ideas to find connections & links, and to make the ideas visible. The more visual skills you build, the more you will be able to think through ideas, find connections, and build momentum around your ideas.

People respond to visuals in ways that they don’t to text. They pay attention to pictures over paragraphs or even bullet-point lists. Drawing and diagramming is a power that lawyers should invest in.

For lawyers specifically, this mindset is about building our communication skills beyond text & speech. As we practice visualizing and prototyping, we can become better communicators. Building our toolset beyond just how we write and how we speak, we can find new ways to engage and direct our audiences with visuals, with interactive media, and with narratives. Design helps us to present information in clearer schematics, and also in more engaging stories.

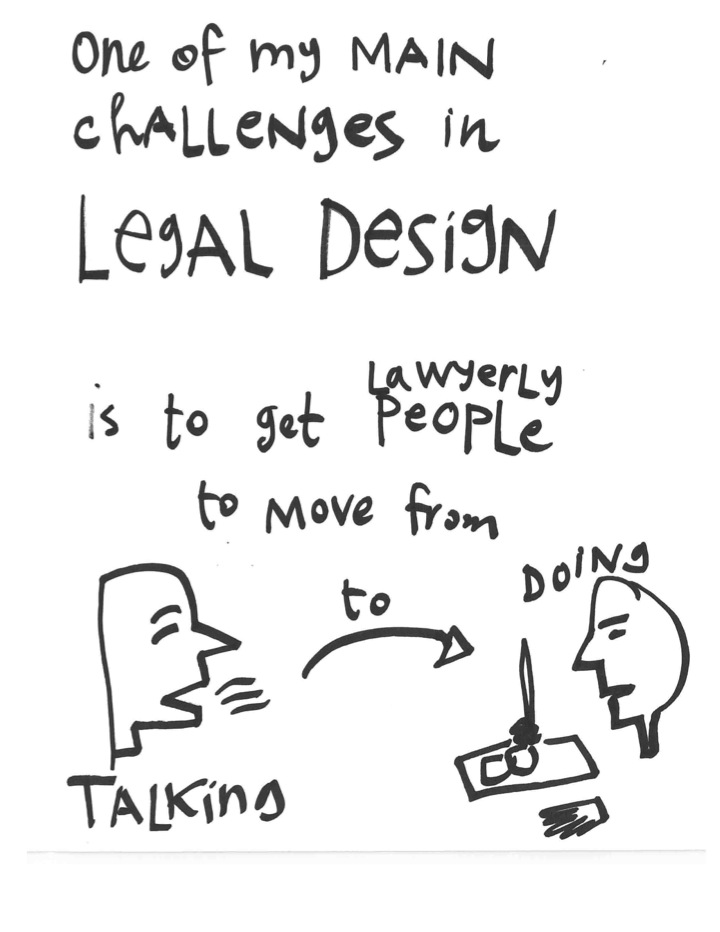

Build to Think

Related to visualization & sketching is Bias to Action & Building to Think. With this mindset we avoid getting stuck in ‘planning’, ‘trying’, or ‘talking about’ what could be done. Rather, we actually build it, create it a rough-and-ready prototype of it.

This is the heart of the agile design process: by starting to build your solution once you’ve conceived of it, the building will help you understand what works or doesn’t. You don’t need to make the full or perfect thing. Rather, it’s about making quick hacks and small versions of the big thing you’re thinking about making.

As you put something together, the act of drawing it, constructing it, or acting it out will help you understand it and see new connections and possibilities. Rather than talking through it, and then ending up in abstract territory, building it brings it back down to human reality and can also get your mind loosened and creativity warmed up.

Making ideas manifest is a key thing. By getting it out of your head, you will think through the details of what functions you’ll provide, and how people will be use it. It also gives you something to test, to see if the idea has the value, viability, and feasibility to actually pursue it.

This approach of “Less Talking, More Making” is a departure from the working style of many lawyers. Rather than talk and discuss ideas on how to get something accomplished or to get to an outcome, the design approach leads us to make & do in order to move forward more quickly.

The ‘made’ thing can help the lawyer refine their own thoughts. It can make their idea much clearer to their partners and audience. It also lets them test and change the thing before creating final versions.

Constrain Yourself

One last mindset is to Embrace Constraints. By working on shorter time cycles, with strict focus, or using a defined process, you can get more creative and more productive. Limits — however annoying or seemingly arbitrary in the moment — can force clearer thought and better focus.

That’s why in workshops and sprints, designers often keep a timer and a set of rules. These can both be abandoned if the situation demands it. But it’s good to have them as constraints to force a limit on what can be done, when it needs to be done by, and what can be ignored and left behind.

Constrained design work is often painful and people resist it. But with a timer ticking, often people can create higher quality output with greater efficiency because they are forced to scrap things that are less important and focus on the core things. Constraints also force action. With a timer, a brief, and a deadline, teams can follow through on prototyping rather than getting stuck in ‘talking’ and ‘thinking’ territory.

How This is Different from Our Usual Ways of Working in Law?

Design mindsets are great complements to the mindsets that lawyers normally use when trying to solve problems. They have value not only when ‘going through a design process to create something new’, but also in how we do our current legal work and education.

By pausing feasibility, diving deeper into user needs, and prototyping and testing quickly, we can get to ideas for new initiatives, tech, and organizational changes that we otherwise would never have thought of. Design can help us envision better ways of working, as well as better way of serving our clients and the public generally. We can draw from interdisciplinary experts whom we invite to collaborate with us. The next chapters will dive into the process to use to actually to get to these new solutions.

21 replies on “2: Design Mindsets”

Margaret,

I am LOVING every bit of this. As a current legal apprentice, I have spent so much time discouraged and feeling stuck, trying to figure out how to learn and communicate the law in a way that feels authentic to me. THIS! Law by Design is it! So thank you for putting this out there even though it’s not your finished project. It has helped me so much already!

Margaret,

I am having a great time all the way from Botswana, Africa reading this. I hope to produce something that will wow everyone here with your mentorship. Looking forward to meeting you soon as a JSK affiliate there at Stanford. All the best.

Great material, it is a new way to think and move legal out of his office and put it close to the clients/users

Dear Margaret, Thank for your generosity. You have inspired me to think differently about how I deliver legal services. I need to collaborate with other professionals to accomplish my goals.

Estou amando cada ideia deste livro!

Estou amando!!!

What a superb creation, excellent loved it, thank you for sharing, I would like this to be read by my Lawyer colleagues…

This doesn’t just help in new product design but in general anything that we try to deliver.

O livro é maravilhoso ! O pensamento através do design é muito rico e inovador e só trará benefícios ao meio jurídico.

Margaret,

Your work is exceptional. I am studying Legal Designer and Visual Law to apply in my petitions and contracts, but mainly to transform the legal language into a simpler understanding for my clients.

Thank for your generosity.

Best regards

Legal professionals are more conservative than we think, so you have presented something ahead of their times.

Look forward to having a hard copy and translating it into Turkish.

ame

Dear Margaret,

Thank you for putting this out there. I have been obsessed with infographics and visual design for the longest time but I silenced it as I felt it didn’t to my role as a Lawyer. Reading your bok had opened my eyes to the amazing ways law can be practised. Thank you.

Esse livro é um abridor de portas. Sou publicitária e estudante de Direito. Ele mescla as áreas envolvidas no Legal Design de forma simples. Parabéns!

This material is for everyone out there who is wanting and willing to make global impact… this material is lucid. Daniel Loveday Agbi, Nigeria.

Esse livro é maravilhoso. Aos poucos o legal design está tomando forma aqui no Brasil, e é simplesmente encantador. Por a advocacia ser uma área muito restrita e elitista poucas pessoas da sociedade conseguem compreender seus direitos. O design sem dúvidas é a melhor forma de comunicar isso de forma assertiva e simples.

Valiosa informacion, gracias!

Excelentes ideas para complementar el mindset de abogados/as.

Excelentes ideas para abogados/as.

Este livro é um exemplo notável de como podemos pensar diferente usando as técnicas disponíveis. Quando encontrei esse “site” nas minhas pesquisas demorei para entender que se tratava de um livro. Ou seja, Hagan, aplicou aqui tudo que ela vem falando sobre Legal Design. Usou uma técnicas já usada (web) e criou um livro acessível por todos. Achei isso realmente inovador.

Thanks for your incredible teaching

Your teaching has been incredibly insightful and transformative for me. The way you present these concepts is both engaging and practical, making it easy to see the real-world applications . I’ve found the lessons not only informative but also inspiring. and they’ve truly helped me grow both professional and personally,

thank you for sharing your knowledge with such a passion and dedication. I deeply appreciate your efforts, and I feel fortunate to have learned from you,

Best regards

Queen Absa

I am really enjoying reading about design thinking and mindsets. Though I feel like I have done many things right, I also feel like I’ve stumbled and been doing much of it deliberately. There are also a ton of things I could have done and can do better. The user-centred, beginner, and multi-disciplinary mindsets particularly are ones I have found most challenging (but beneficial).